Asking students to use books for research sometimes feels old-fashioned even to me, an inveterate reader. So much exists online, in subscription databases and on the free web, and students instinctively reach for their phones or a keyboard to discover information. Yet doing research for my own master’s degree in history over the past few years… Continue reading

Category: Research

“On the Best Days, Our Students Teach Us,” MiddleWeb

This week it has been even more of a pleasure than usual to spend time with eighth graders. They’ve been creating social reform concept maps, an oldie-but-goodie project that I… Continue reading

“Can I Have a Do-Over? A Debate Gone Awry,” MiddleWeb

Most days, I feel reasonably positive about how my classes have gone, in this my 19th year of teaching. I usually have in mind tweaks or even overhauls for next year’s version of that topic, but rarely do I feel that an entire project has fallen short of my expectations. But last month… Continue reading

“Meaningful Discussions with Nonfiction Texts,” CommonLit

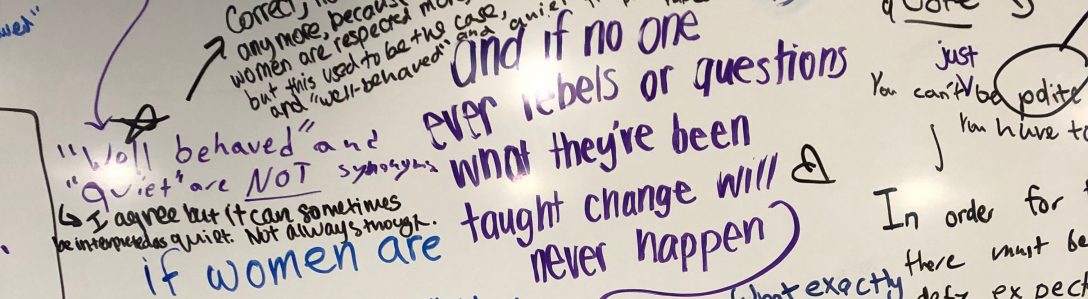

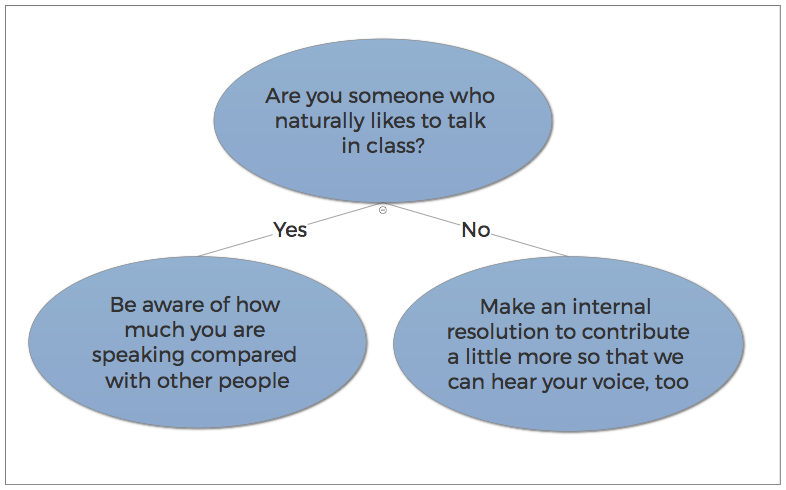

Participation has always been one of the most difficult things to assess and encourage for my 8th grade history students. Sometimes the quietest students in discussion are the most devoted in their writing, and sometimes the most vocal students are not aware… Continue reading

“How Three 1970s Musicals Probed Disillusionment with the American Dream,” Master’s Thesis, 2017

Three Broadway musicals from throughout the 1970s – Follies, A Chorus Line, and Annie – in the intentions of their creators and actors, in the reception by critics and audiences, and in the messages of the book and music themselves – reflected larger social issues of the time… Continue reading

“Total War: Wrestling with a Scholarly Article,” MiddleWeb

In a never-ending search to infuse garlic and oregano into the plain marinara sauce of textbook history, sometimes I ask students to read a scholarly journal article or a chapter of a popular history book… Continue reading

“Can’t I Just Choose My Own Topic?” Edutopia

So many times as an English and history teacher, I’ve rushed students through the first step of the research process: choosing a topic. Then we can move on to the real work — or so I’ve always thought. Recently, however… Continue reading

“‘8 Ways to Make Middle School History More Meaningful,'” MiddleWeb

At the end of every year, like so many history teachers, I regret simply skimming the surface of the past. Three weeks, and there went India. We spent half a day on Emperor Ashoka, and I completely glossed over… Continue reading

“Making Notecards Exciting (Really!),” Stenhouse Publishers Blog

I loved doing research notecards as a child.

A family legend from third grade has me standing in the living room, cards in hand, smocked dress ironed, hair pixie-cut, ready to rehearse a three-minute talk.

“Bats,” I enunciated in my sharpest, most Hermione Granger voice.

I could organize my world, and the World Book Encyclopedia entry, in the space of three by five inches.

Needless to say, research notecards have never been quite as popular for most of the eighth graders I teach.

They understand why our history department requires the cards in grades 7 through 9 as a foundation, before students choose their own organizational method in grades 10 through 12. The cards help them avoid plagiarism, weave together facts, and create arguments based on other people’s research.

But that doesn’t mean they like doing them. The process is seriously detail-oriented.

So this year, when I returned to teaching history after four years of English, I wanted to find a way to make notecards fun, or at least a little snazzy.

At first I was reluctant to try electronic notecards because I didn’t want to lose the tangible moment of spreading and stacking cards to create an outline. But after realizing that students could still sort cards printed on half-sheets of paper – and after learning that our ninth-grade history team was switching over to electronic cards this year – I was convinced.

Our library has introduced the history department to NoodleTools, and I love the program for its power and one-stop shopping for research skills. (It does require an annual fee for your school or district. Some teachers also like free programs, such as EverNote or NoteStar, or set up a template in Microsoft Word or Google Docs.)

The brilliance of the notecard structure is just how much it includes – and that it forces students to think.

This spring, for each of fifteen notecards for a project on an American reformer’s successful tactics or strategies, I asked students to fill in the following fields on the program’s template:

- Title (Main Idea). Giving each card a heading helps with organization.

- Source. Students select a source from a drop-down menu based on their Works Cited list, and the information instantly links to the card.

- Direct Quotation. Students copy and paste – or type in, from a book – a sentence or two.

- Paraphrase. The direct quotation, paraphrased.

Steps 3 and 4 are what I like to call the “anti-plagiarism cocktail.” In the past, I’ve flipped through copies of sources at the back of a research paper to find the sentences that students had paraphrased. This time, as I was grading, I could instantly check quotations and paraphrases together.

- My Ideas. For each card, students wrote a sentence on how the fact showed the reformer’s tactics, methods, strategies, or personality.

By the time students completed the cards, especially the “My Ideas” sections, they had little trouble brainstorming a topic sentence for a 300-word paragraph on their reformer. In contrast, with handwritten cards in the past, students rarely understood they were heading toward an argument.

As with any new project, there were stumbling blocks from my lack of direction:

- Students copied too much into the direct quotation box, making it difficult to paraphrase effectively.

- Students sometimes paraphrased so generally as to make the information meaningless. For example, a few said that their reformer attended a lot of schools, instead of noting which schools were important to the person’s education and why.

- Some of the “My Ideas” comments were too similar from notecard to notecard. Next time I will suggest commenting on that specific fact on that particular notecard.

- The notecards consumed a lot of class and homework time. To complete them, students had one 43-minute period and one 77-minute period, plus three nights of homework, and some still had to push to finish.

- Some students were annoyed that they didn’t use all the notecards for their analytical paragraph. This was by design, and I told them beforehand that they should use about half. Next time, however, I will require ten or twelve cards instead of fifteen, as many suggested, and also talk with students more about why they shouldn’t use everything they find.

James M. McPherson’s “iceberg principle,” from the preface to his excellent For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, is a good rule of thumb: “Only one-seventh of an iceberg is visible above the water’s surface. Likewise the evidence for soldiers’ motivations and opinions and actions…represents only the iceberg tip of the evidence accumulated in my research. For every statement by a soldier quoted herein, at least six more lie below the surface in my notecards.”

At the end of the project, anonymous student feedback tilted toward the cards’ being worthwhile. Although about ten percent said that “the notecards didn’t help very much,” “took a long time,” and “seemed too formal,” about twice that many said, “I liked having the notecards to write the essay” and “Although the notecards seemed hard at first, they made writing the paper a lot easier.”

For me, the depth of students’ thinking means that doing notecards this way in the future will be a no-brainer. Research will still be painstaking work, but the appeal of the electronic means that more of my students may find their own Zen-like 3”x 5” card moments, just as I did in third grade the old-fashioned way.

This post originally appeared on the Stenhouse Publishers blog in April 2014.

“Irving J. Gill, Progressive Architect, Part 2: Creating a Sense of Place,” Journal of San Diego History

By 1908, Irving J. Gill was a well-established San Diego architect. Since arriving from Chicago in 1893, he had experimented with many styles, won loyal clients, and made a name for himself among the community’s leading citizens, Progressive and otherwise. But his mature style… Continue reading